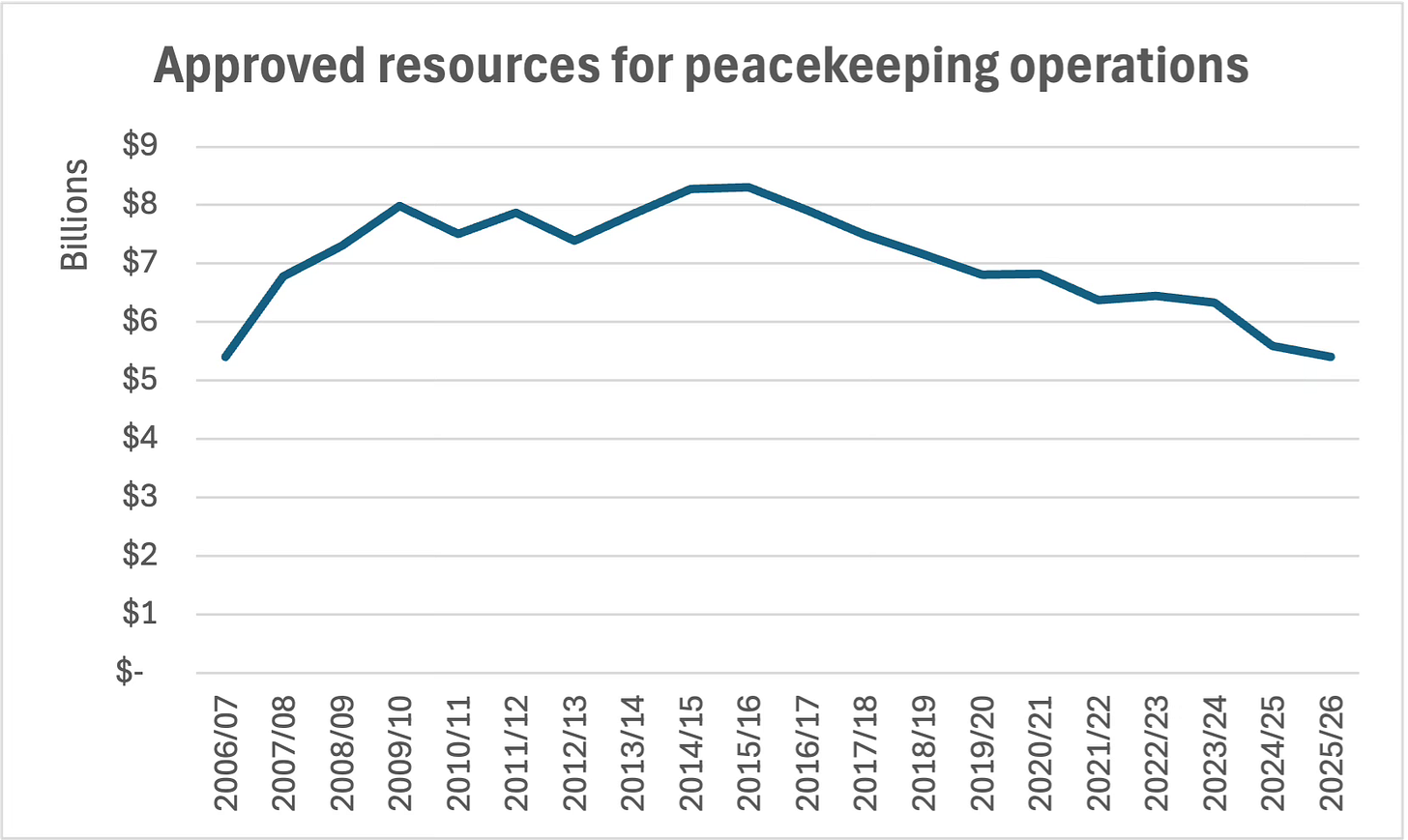

Last week, the Fifth Committee of the General Assembly concluded the second part of its resumed 79th session by approving nearly $5.4 billion in resources for peacekeeping operations for the 2025/26 financial period. The $5.4 billion figure represents a continuation of the ongoing decade-long retrenchment of peacekeeping operations. It also reflects a cut of approximately $112 million from the level requested by the Secretary-General and comes at a time when the Secretariat has become increasingly vocal in asserting that the failure of Member States to provide sufficient resources is a limiting factor in the impact of peacekeeping operations.

I am not personally convinced that the challenges faced by peacekeeping operations stem from resource constraints. As I’ve argued previously, missions suffer from a lack of focus on political solutions, templated approaches to mission design and mandate implementation, and friction with other UN entities and organizations, all of which point to the need for new approaches rather than more resources. But even if we accept the assertion that missions are under-resourced, an examination of why this is the case shows that the blame directed at Member States obscures the effect of internal Secretariat dynamics on budget cuts. These internal dynamics are not only relevant when considering the management of peacekeeping operations, but also of the development and implementation of broader reforms across the Secretariat.

Peacekeeping budgets in context

The overall level of resources for peacekeeping today is approximately the level it was twenty years ago, at the end of the 2006/07 financial period. However, the amount approved for the support account (the budget for the backstopping capacities at Headquarters for peacekeeping operations) is currently over $425 million, which is more than double the level in 2006/07, when the General Assembly approved $189 million, and still significantly higher than the $231 million level in 2007/08, during which the General Assembly significantly enhanced the backstopping capacities at Headquarters—including through the establishment of the Department of Field Support (now the Department of Operational Support), the Office of Military Affairs, and the Office of Rule of Law and Security Institutions—to manage what was then significant expansion in peacekeeping operations. The demand for UN peace operations have changed dramatically over the course of the past 20 years, but this is not reflected in the machinery that has been built up at Headquarters.

This has not gone unnoticed as part of the Secretary-General’s UN80 initiative. But the measures proposed thus far are inadequate to overcome mindsets and structures that have become entrenched over the past three decades. The Secretary-General, clearly frustrated by the lack of willingness of the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and the Department of Peace Operations (DPO) to contemplate meaningful reform, singled out the two departments in his 12 May briefing to Member States on UN80, calling for “resetting DPPA and DPO, merging units, eliminating functional and structural duplications, getting rid of functions that are also exercised in other parts of the system” and suggesting that staffing in the two departments could be reduced by 20%. Not surprisingly, the departments in question have a different view, expressing a preference for “coherence, not consolidation”, during the 24 June briefing to Member States. But making peace operations fit for purpose is not something that can be rectified by simply cutting staff or improving coordination mechanisms; doing so requires a complete re-think of both the capacities that exist at Headquarters and how they operate.

Blaming the Member States

The Secretariat often claims that peacekeeping operations are under-resourced, and that Member States are to blame. For example, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, Under-Secretary-General for Peace Operations, argued in Foreign Affairs that the failure of Member States to adequately resource peacekeeping operations limits missions to the “intermediate goals of preserving cease-fires and protecting civilians”. As a result, missions can therefore “only prevent a bad situation from getting worse, not help build a path to peace.”1 But the cuts made by the General Assembly in the 2025/26 budgets amounted to just 2% of the amount requested by the Secretary-General. This is in line with the average levels of cuts in recent years, which has averaged around 1.5%. It is hard to believe that reductions in the order of 1.5% are what has prevented peacekeeping operations from effectively implementing their mandates.

Cash shortfalls

Of course, peacekeeping operations are not immune to the liquidity challenges that have become particularly acute in recent years. These challenges are primarily driven by the failure of the two largest financial contributors—the United States and China, which are responsible for approximately 26.2% and 23.8% of peacekeeping budgets, respectively—to meet their financial obligations to the UN. But liquidity challenges are not sufficient to explain the difficulties missions experience in effectively implementing their mandates and demonstrating impact on the ground. This is because peacekeeping operations have been able to mitigate much of the operational impact of cash shortfalls by drawing upon a range of liquidity management measures, including cross-borrowing and tapping into the Peacekeeping Reserve Fund, as well as the practice of delaying reimbursements to troop- and police-contributing countries (which currently account for over 40% of the total expenses budgeted for peacekeeping).2

Bureaucratic politics

If under-resourcing of missions can’t be adequately explained by cuts by the General Assembly or liquidity concerns, it’s worth looking at internal Secretariat processes and practices. The Secretariat regularly engages in self-censorship in its budget requests, attempting to pre-empt expected cuts by the General Assembly by not fully requesting the resources required to implement mandates. This is a version of what has been described as the “anticipatory veto”, the tendency of Secretariat officials to propose what they think Member States are likely to endorse.3 Such cuts happen even when missions have been given new mandated tasks, and when the justification for additional resources is strongest. In such cases the Secretariat sometimes resorts to seeking capacity through voluntary contributions instead of requesting resources through mission budgets, as in the case of climate, peace and security advisors deployed to missions with climate-related mandates.

This practice of self-censorship in budget requests fails to recognize the fact that budget cuts have a performative nature; they can be simultaneously symbolic and substantive. For both the Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions and the Fifth Committee, budget cuts are a way to assert their respective oversight roles over the Secretariat. For major financial contributors, budget cuts are a way to show commitment to prudent financial stewardship or to signal policy preferences. And for individual delegates, budget cuts can be a way to quantifiably demonstrate impact to their managers and to their counterparts in capital. Preemptive cuts are therefore counterproductive as, regardless of whether the Secretariat makes preemptive budget cuts, there are strong incentives for the General Assembly to seek reductions regardless of the degree of austerity reflected in the proposal of the Secretary-General.

It is the proximity to intergovernmental processes and distance from operational implementation that makes staff at Headquarters particularly susceptible to making preemptive budget cuts, and the persistence of this practice in mission budgets demonstrates the continued dominance of Headquarters in the budget process. This is despite the fact that the management reforms that entered into effect in 2019—including both the reorganization of departments at Headquarters and the implementation of a new delegation of authority framework—were supposed to shift the center of gravity to the field by providing heads of missions with authority over resource management. Those reforms should therefore have led to field-driven budgets that better reflect operational realities and requirements. Instead, the office of the Controller at Headquarters continues to decide in practice what is included in the budgets presented to the General Assembly. If peacekeeping operations are under-resourced, it is disingenuous for the Secretariat to blame Member States for cuts when it is the Secretariat itself that fails to present for consideration the level of resources required for the implementation of mandates.

Bottom line

At a time where the number of conflicts has reached a historic high, UN peace operations can play an important role in reducing violence and supporting countries on a path towards sustainable peace. Whether or not under-resourcing is what prevents peace operations from maximizing impact in the achievement of their mandates, the manner in which the Secretariat approaches peacekeeping budgeting demonstrates some of the shortcomings of existing approaches and structures.

However, many improvements in these areas were promised by the Secretary-General during his first term as part of the management reforms and the restructuring of the peace and security pillar. Unfortunately, few of those benefits have materialized and not enough has changed in either form or function. The UN80 initiative can be an opportunity to make necessary changes, but any proposals presented must reflect lessons learned from previous efforts. A frank and honest assessment of why earlier reforms fell short is necessary for new proposals to be credible.

Lacroix, Jean-Pierre. “Peacekeepers Need Peacemakers: What the UN and Its Members Owe the Blue Helmets.” Foreign Affairs (blog), September 2, 2024. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/united-nations-peacekeeping-missions.

This having been said, the increasing levels of unpaid assessments for peacekeeping are beginning to reach a level that threaten to exacerbate liquidity challenges to a level beyond what can be managed through existing measures approved by the General Assembly.

Salton, Herman T. Dangerous Diplomacy. Oxford University Press, 2017. 24-28. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198733591.001.0001.