Considerations for a new vision for peace operations

Remarks to the Strategic Police Advisory Group

For this week’s commentary, I am sharing the scene-setter remarks I delivered during a panel discussion hosted by the Strategic Police Advisory Group last week on the development of a new strategic vision and strategic framework for UN Police.

Any meaningful discussion on the development of a strategic vision and framework for UN Police must be situated within a broader reflection of the role and future of the UN in the maintenance of international peace and security. It must also take into account the internal context within the UN system and the external context of the tectonic shifts underway in the international system.

Internal UN context

For those of us working on peace operations in New York, when we think of police we instinctively think of UN Police—that is, the Police Division in the Department of Peace Operations and police components in missions. But the Police Division and police components are not the totality of policing at the UN. For example, there are over a dozen separate UN entities in the inter-agency task force on policing, each with their own governing bodies, mandates, and programs.1 This fragmentation is mirrored in member states and their permanent missions, each of which has separate peacekeeping, peacebuilding, police, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, development, and budget experts who cover parallel intergovernmental processes and do not coordinate nearly as much as they should.

An exercise focused narrowly on defining a strategic vision and framework for UN Police without taking into account the capacity and expertise on police and policing-related issues across the UN system may feed mission creep and exacerbate interdepartmental rivalries. Member states risk being drawn into ongoing bureaucratic turf wars when they are asked to endorse new or expanded mandates for individual UN entities. We should therefore be taking a broader view of police and policing at the UN, one focused on improving the coherence and impact of UN efforts as a whole. Form must follow function. Comparative advantage, not bureaucratic ambition, should drive the division of responsibilities amongst sources of capacity and expertise, both inside and outside the UN.

At a time when many missions have closed and many others are in drawdown, we also need to think in terms of UN transitions and to better support non-mission settings. This requires reducing the administrative and cultural barriers to allowing the UN development system with access to expertise from the peace and security pillar, when and where appropriate. But it also requires recognizing the fundamentally different principles and priorities of UN country teams. We need to avoid the instinct to shoehorn approaches and expectations from peacekeeping into non-mission settings.

We also need to recognize that whatever vision and framework is adopted needs to be underpinned by an appropriate administrative and financial framework. The 2026 meeting of the Working Group on Contingent-Owned Equipment recently concluded its work, and though some adjustments were recommended, we need to acknowledge that the current system we have, one created in 1996, is fundamentally flawed. It does not create the correct incentives for performance and accountability, it does not reflect the operational realities in the environments in which we operate, and it does not enable generation of the specialized capabilities and equipment we need.

Broader international context

Zooming out from internal processes and structures, we can’t ignore the general decline in commitment to the tenets of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. These are the principles that have underpinned peacebuilding at the UN since it was first introduced at the UN in 1992 in An Agenda for Peace.

We see this declining commitment in the Security Council, where the repudiation by the United States of the ideals of the rules-based international order significantly changes the types of missions and mandates likely to be approved. The promotion of norms and values is out; the use of force is in.

We see this declining commitment in host countries, where governments increasingly see democracy, human rights, and the rule of law not as the foundation for sustainable peace, but as fundamental threats to their authority. What host governments want out of multilateral interventions is not peacemaking or peacebuilding, but rather military force to help them defeat their opponents and stay in power.2 This has contributed to the trend away from UN peace operations towards securitized alternatives. To add insult to injury, this substitution effect has been accompanied by the relegation of the role of the UN to that of a logistical service provider and paymaster.3

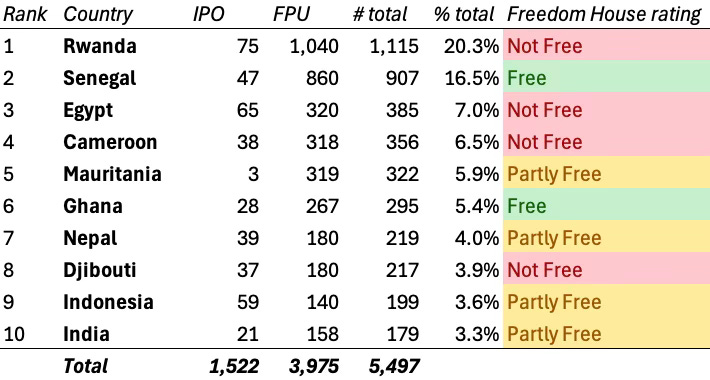

We see this declining commitment in our troop- and police-contributing countries, in which few major contributors are credible champions of political rights and civil liberties.4 Of the top ten police-contributing countries today, only two are rated “free” in the latest Freedom House index. Four are “not free” and four are “partly free”.

Together, these shifts have pernicious effects. Over the past decade, evidence has grown of the negative unintended consequences of stabilization, including on protection of civilians, safety and security of peacekeepers, humanitarian access, human rights, peacebuilding, and political processes.5 Research published last year by academics in the United Kingdom illustrated how UN peace operations unintentionally enable authoritarianism in host countries. This primarily happens because peace operations materially enhance the capability of host state security forces and because peace operations fail to impose meaningful consequences for violations of international norms and laws by host governments.6 We cannot ignore the fact that capacity building efforts and other activities undertaken by UN Police in peace operations have contributed to these adverse outcomes.

Looking forward

Any new vision for UN Police must contend with the congested internal landscape of the UN system, the changing demand for peace operations, and the legacy of past and present efforts to support host state security forces. For a brave new world, we need a brave new vision.

Should the UN help countries build peace through the fostering of pluralist societies or should it do so by promoting stability through the strengthening of tools of repression?7 To what extent should the UN compromise on its principles to meet the changing preferences of the Security Council and host governments? And how can the Secretariat and member states better utilize the General Assembly at a time when the Security Council finds itself increasingly deadlocked? These should be guiding questions for developing a new vision for both UN peace operations and UN policing.

That having been said, the forthcoming report of the Secretary-General on the peace operations review will likely fall far short of both what we expect and what we need for the current moment. At a time of retrenchment and fiscal austerity, the defensive reflexes of departmental leadership prevent the UN from being able to engage in a clear-eyed reflection on the necessary shifts.8 We should therefore see the report as the start, rather than the end, of a process of reflection and an opportunity to chart a new path forward for UN peace operations and for UN police. An independent perspective may be required.

We must push back when the Secretariat argues that the existing toolkit works and that recent setbacks are entirely due to inadequate political and financial support from member states. The decade-long retrenchment we have experienced in UN peace operations should be a wake-up call that existing approaches are no longer fit for purpose to respond to contemporary demands and requirements. Any new vision must contend with the changed international environment and address the shortcomings of current approaches, including its entrenched siloes.

In turn, this vision must be supported through the realignment of structures, policies, and administrative frameworks. The systems and approaches in place today still fundamentally derive from structures and processes put in place in the 1990s, but the landscape has changed dramatically in the past 30 years. The UN must be able to draw from available capacities and expertise from inside and outside the organization. The future configuration and role of UN Police in support of this vision should be defined by its strengths and not its aspirations.

© 2026 Eugene Chen under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University.

The members of the inter-agency task force on policing (IATF-P) are listed in the footnote of General Assembly resolution 77/241

Williams, P. D. (2024). Multilateral counterinsurgency in East Africa. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2024.2372712

Karlsrud, J. (2023). ‘Pragmatic Peacekeeping’ in Practice: Exit Liberal Peacekeeping, Enter UN Support Missions? Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 17(3), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2023.2198285

Coleman, K. P., & Job, B. L. (2021). How Africa and China may shape UN peacekeeping beyond the liberal international order. International Affairs, 97(5), 1451–1468. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab113

Hunt, C. T. (2017). All necessary means to what ends? The unintended consequences of the ‘robust turn’ in UN peace operations. International Peacekeeping, 24(1), 108–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2016.1214074

von Billerbeck, S., Gippert, B. J., Oksamytna, K., & Tansey, O. (2025). United Nations Peacekeeping and the Politics of Authoritarianism (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780191925474.001.0001

Paris, R. (2024). The future of UN peace operations: Pragmatism, pluralism or statism? International Affairs, iiae182. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiae182

Christian, B. (2024). Why International Organizations Don’t Learn: Dissent Suppression as a Source of IO Dysfunction. International Studies Quarterly, 69(1), sqaf008. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaf008