Fifth Committee post-mortem

The death spiral begins

Fifth Committee deliberations on the proposed programme budget for 2026 and other administrative and budgetary questions dragged on past Christmas, and it was not until 30 December that the General Assembly considered the reports of the Fifth Committee and adopted resolutions on the budget. These decisions essentially endorsed the additional budget cuts proposed by the Secretary-General under his UN80 revised estimates, but without measures that would help alleviate the cash crisis despite the fact that the budget cuts will exacerbate an already precarious liquidity situation.

Unless major changes in how budgets are prepared and considered are made by the Secretariat and Member States, the failure of the United States to pay what it owes to the UN will mean that the organization is now locked in a budgetary death spiral that will severely undermine its ability to implement intergovernmental mandates in the years to come.

Outcomes

The General Assembly approved a top-line figure of $3.45 billion for 2026, though the actual amount to be assessed will be lower given the approximately $299 million in underspend from 2024 that will be returned to Member States in credits. The end result is a budget level that is essentially a 15% reduction from the $3.81 billion approved for 2025.

Many Member States had substantive and procedural misgivings about the revised estimates. These included frustration about the short amount of time (less than a month) available for the Fifth Committee to consider the proposal and the lack of clarity on the methodology used to determine the reductions presented. They also included concerns about the impact of the proposed cuts on mandate implementation and the fact that the cuts appeared to affect certain pillars of the Organization more than others. But in the end the General Assembly largely ended up agreeing to the proposals despite the broad discontent and the lack of clarity because Member States were not going to turn down an opportunity to reduce their assessed contributions.

The death spiral, explained

The extraordinary effort to identify additional cost savings under UN80 and reflect them in the 2026 budget as revised estimates, first announced on 12 May, was in large part an attempt by the Secretary-General to demonstrate a commitment to cost-cutting and reform to the Trump administration in the hopes of getting the administration to meet its financial obligations to the organization. This was a big gamble; in the best case, the United States would continue its practice of late payment and the UN would continue limping on.

But the gamble did not pay off. The Trump administration not only rescinded funding that had already been appropriated in previous years to pay its assessed contributions, but declined to request the necessary funding in its FY 2026 budget request. And the UN is now left with a budget cut that further reduces the amount of funding available to implement the same portfolio of mandates.

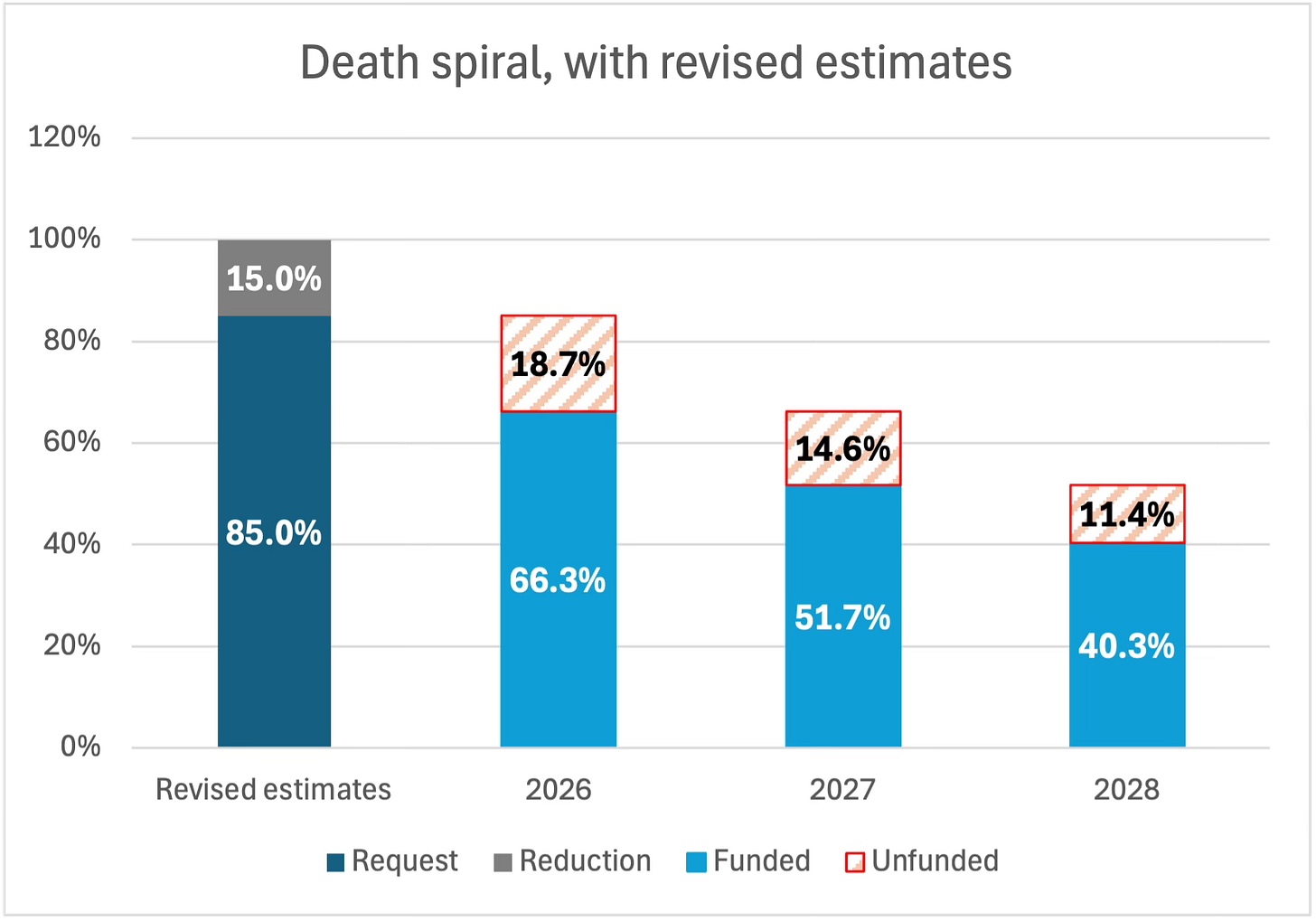

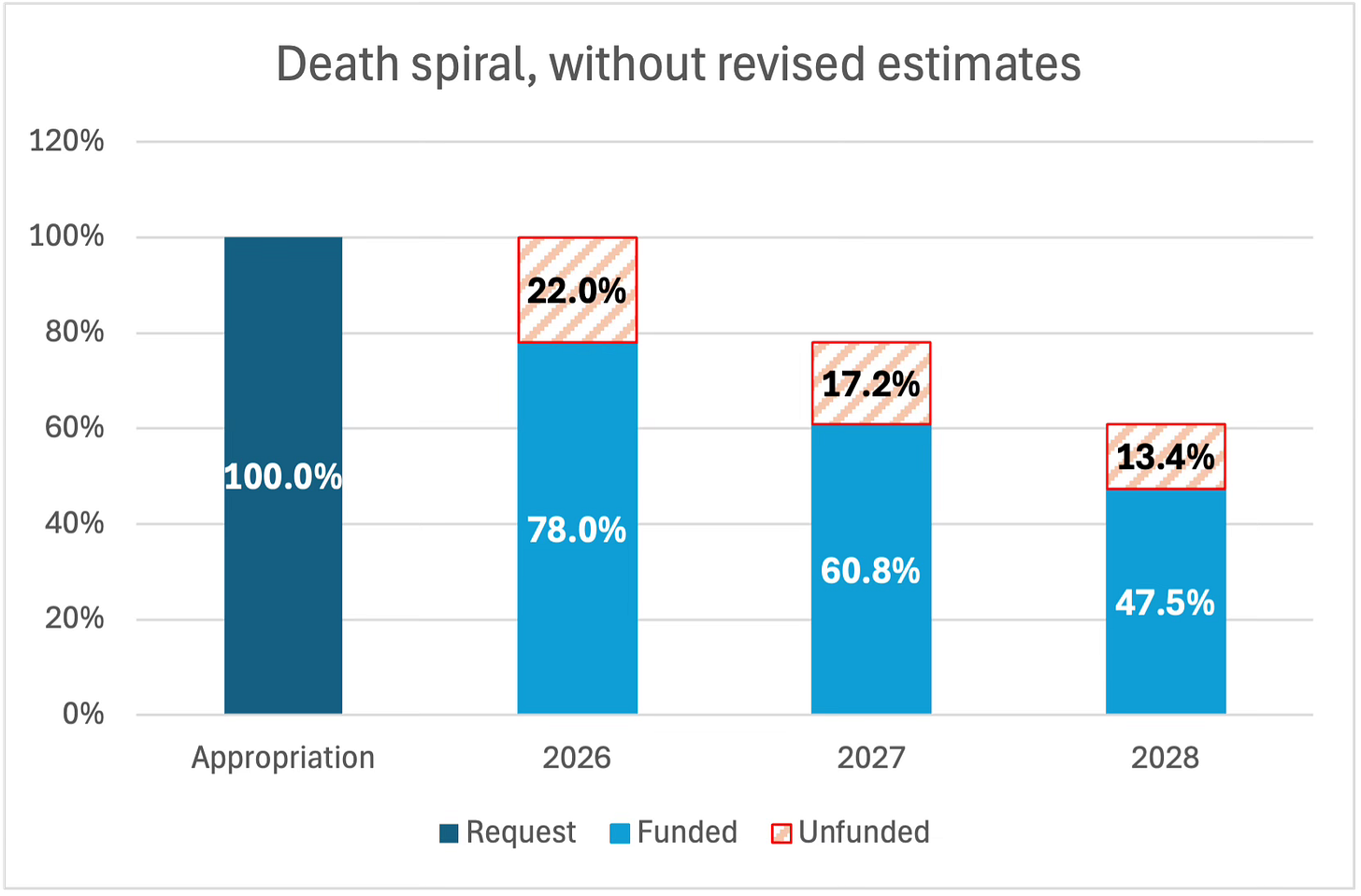

This chart illustrates, in highly simplified terms, the effect of a budget cut on the funding available to the Secretariat and the cumulative effect over time. A budget cut is not an effective response to a cash shortfall. The fundamental problem is that the United States is not paying its 22% share of the regular budget, and no level of budget cut will ameliorate this, as the remainder after the cut will still be missing the 22% share owed by the United States. What appears to be a 15% cut on paper actually means that the level of contributions the Secretariat can expect to receive is less than two thirds of the level of the previous approved budget.1 And since current year budget implementation projections are the basis for the preparation of the next year’s budget, this problem will only worsen over time.

Expenditure reductions, on the other hand, are a way of managing within existing budgets to avoid spending beyond expected contributions; this is what the Secretariat had been doing under the regular budget and is the essence of the contingency plan in place for peacekeeping operations.

The Secretary-General could have implemented efficiency measures to reduce expenditure within the original 2026 regular budget request to match expected contribution levels without proposing a further budget cut. Had he done so, the death spiral would not have been averted, but the cash position of the Organization would not be quite as dire.

No action on liquidity measures

The General Assembly declined to take any action on proposals to address liquidity, including the request of the Secretary-General to be able to retain unspent funds.

To many outside observers, the failure of the General Assembly to approve this seemingly obvious measure appears bewildering. But it makes more sense from the perspective of Member States who have been paying in full and on time; to them, the retention of their excess contributions to cover shortfalls from countries who have failed to meet their financial obligations not only penalizes those Member States who pay, but also reduces the pressure on deadbeat countries to pay up.

This concern about fairness helps to explain the one change that the General Assembly did approve on the use of unspent balances:

Decides that, starting from January 2026, regular budget credits to be apportioned among Member States in accordance with the Financial Regulations and Rules shall offset regular budget arrears of Member States, before crediting to the assessments, and the Financial Regulations and Rules shall be amended accordingly;2

In other words, only Member States who have met their financial obligations could apply their share of unspent 2024 balances against their 2026 assessments. For all other Member States, unspent balances could only be used to reduce their regular budget arrears.3

Missed opportunities on personnel matters

Personnel costs are a major cost driver for the organizations of the UN system, and a re-thinking of whether all of the elements of the existing compensation system—including both take-home pay and allowances—continue to make sense individually and collectively is long overdue. After all, there have been considerable changes in workforce demographics and evolution in mandate implementation requirements since the various elements were originally introduced. In many cases, the manner in which benefits and entitlements have been calculated, updated, and applied over successive decades has become increasingly disconnected from the original rationales and needs that drove their introduction in the first place.

But the loud push by the United States and others this session to reduce the benefits and entitlements of UN staff members, such as education grant, ultimately came to nought. It isn’t entirely clear why they ultimately gave in, though it is not unusual for delegations negotiating in bodies that operate on the basis of consensus to begin with maximalist starting positions in order to try to land in a more acceptable compromise during the end game.

The General Assembly did signal a willingness to reconsider the relationship between net remuneration of UN staff in the Professional and higher categories and those in the comparator, the U.S. federal civil service.4 Although this may lead to an adjustment to the net remuneration margin next year when the Fifth Committee considers the results of the comprehensive review of the compensation package, the absence of clear guidance by the General Assembly on entitlements and benefits is likely to mean that the review conducted by the International Civil Service Commission is a limited one that focuses on how existing elements of the package are calculated, rather than the fundamental rethink of salaries, benefits, and conditions of service that is badly needed.

Looking ahead

The end result of all of this is that the UN enters 2026 in a dramatically worsened financial position. It will likely have less cash to implement the same range of mandates to respond to urgent demands in a world best by interconnected and worsening crises. The great tragedy, of course, is that this outcome was both entirely unnecessary and entirely foreseeable.

Regardless of how we got here, we’re now at the start of a budgetary spiral and need to try to find ways out. My assumption is that the United States is going to continue to fail to honour its financial commitments to the UN. The fact that only certain entities were singled out in last week’s presidential memo on the U.S. withdrawal from international organizations does not suggest to me that funding for the rest of the UN will be forthcoming.

From a budgetary perspective, some degree of buffer could be built into budgets to account for contributions not expected to be received, but this is a major departure from budgetary practice; not only would it require the Secretariat, the Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions, and the Fifth Committee to operate with an improbable degree of open-mindedness and civic-mindedness, but is also unlikely because it would entail all other Member States paying more to cover for deadbeat countries.

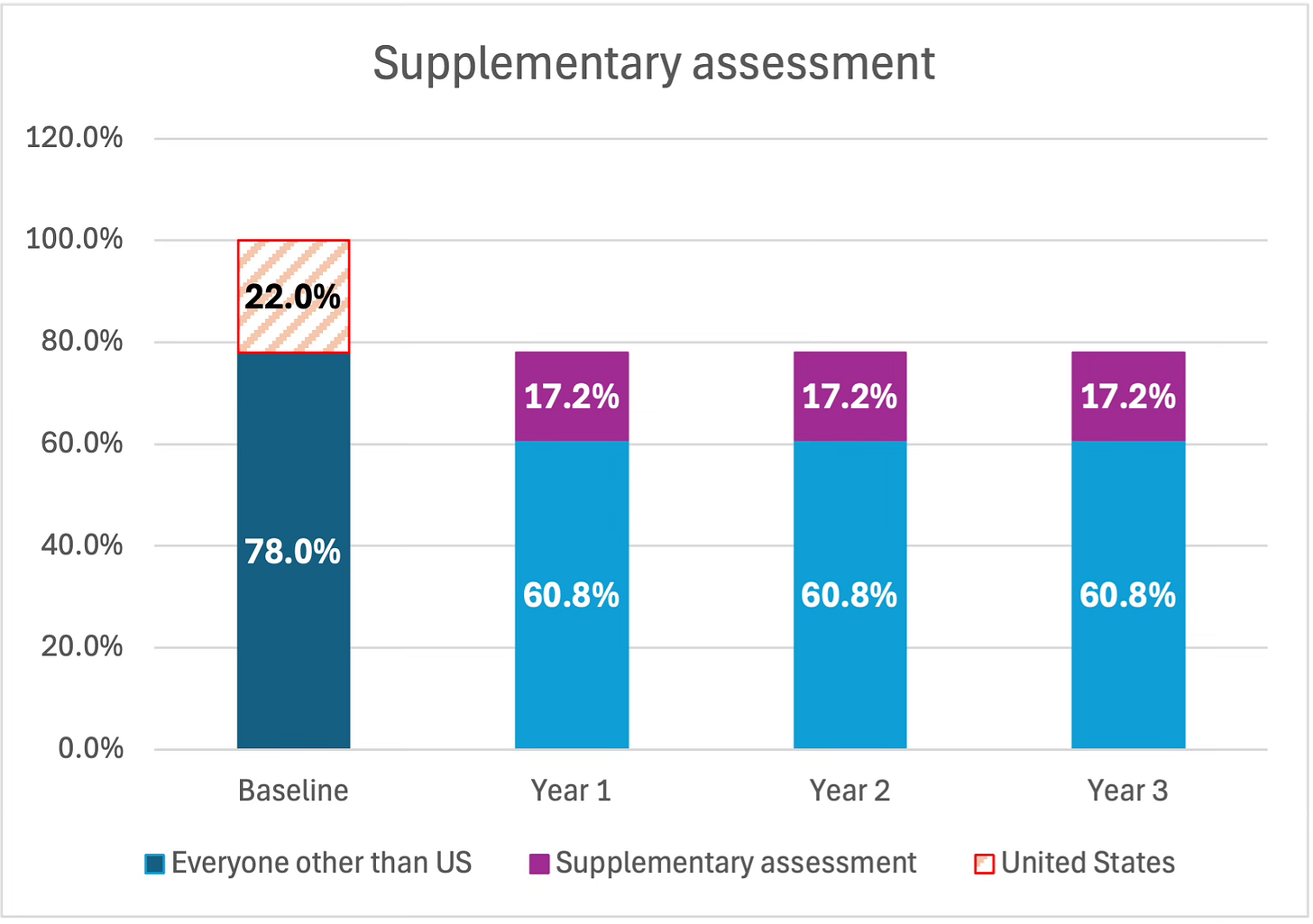

As I’ve previously argued, another way to break out of the budgetary death spiral is for the Secretary-General to be authorized to issue a supplementary assessment, essentially be a loan provided by other Member States to cover shortfalls from non-payment. Admittedly, getting Member States to agree would be a heavy political lift and would require a major political and financial crisis to make happen. It just so happens that one is just over the horizon, namely the fact that the United States will cross the Article 19 threshold soon unless it begins making substantial payments.

The combination of a budget cut and supplementary assessment would have three important effects:

Member States other than those in arrears under Article 19 pay the same amount as they did the previous year.

Member States in arrears under Article 19 would be responsible for repaying the supplementary assessment in addition to their “normal” arrears, therefore ensuring that there is no reward for bad behavior.

The cash shortfall is addressed, thus avoiding the death spiral.

Final thoughts

Beyond the dire financial situation, the UN also has to contend with another major consequence of the non-payment of contributions by the Trump administration that will have far-ranging effects this year and beyond. China has now displaced the United States as the largest effective financial contributor to the UN under assessed contributions and will be able to leverage this fact to be able to play a larger formal and informal leadership role in steering the direction of the Organization.

© 2026 Eugene Chen under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University.

And that’s assuming that the United States is the only Member State not paying its contributions in full. In fact, 42 Member States failed to pay in full in 2025.

General Assembly resolution 80/243 section XIV, paragraph 3

General Assembly resolution 80/244C, paragraph 3.

General Assembly resolution 80/236, paragraph 12.

Eugene - Keep up the great work. We all depend on it! You might find of interest a new Substack resource https://multilateralaccountability.substack.com/